When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here's how it works. |

Canon’s lens technology has led the industry in innovation. Canon's ability to develop excellent lenses is fundamentally derived from lens elements and coatings designed to correct optical defects such as aberration, flare, and distortion. This lens technology has allowed Canon to manufacture compact, high-quality lenses while maintaining consistency in sharpness and minimizing aberrations under various shooting conditions. This article describes the elements and coatings used in Canon’s lenses.

Elements

Aspherical Lens Elements

Normal elements cannot make parallel light rays converge into a single point. This leads to aberrations called spherical aberration. Aspherical lenses feature non-spherical surfaces engineered to focus light rays to a single point.

The above diagram shows the aspherical surface greatly exaggerated. In real life, the variation is almost impossible to see. Using these elements and correcting for spherical aberrations assists in ensuring sharp images, particularly at wide apertures, and enables compact lens designs with fewer elements, thus reducing weight and cost. As well, depending on where the aspherical element is in the optical design, aspherical elements can also assist in the correction of distortion.

The tolerances required by these elements are impressive. As Canon noted

Today, aspherical lens elements are so precisely ground and polished that if the degree of asphericity is even 0.02 micron (1/50,000th of a millimetre) away from ideal, the element is rejected.

Canon employs several aspherical element variants:

- Ground Aspherical

- Plastic Molded Asphericals (PMo)

- Glass Molded (GMo)

- Replica Aspherical

Canon is the only lens manufacturer to employ four different methods of producing aspherical elements.

Many of the reasons for the different methods are the cost of manufacturing in both materials and the time required to produce the element. If the lens is mass-produced in significant quantities, then Canon needs to use an aspherical element production method that will create enough of these elements to support the assembly lines.

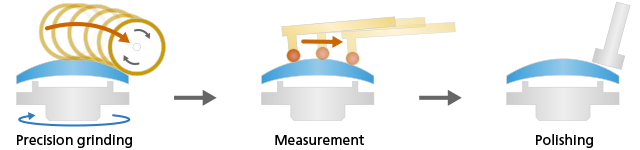

Ground Aspherical

Canon’s ground aspherical elements are crafted by grinding and polishing glass into non-spherical shapes. This process is suitable for different types of glass and can also be used to provide aspherical elements of large diameters. Because of this flexibility, it allows the optical designers the freedom to develop lens optical designs with the best possible optical quality.

The grinding and polishing technique is labor-intensive and thus costly. Canon atypically reserves these elements for its L professional, cinema, and broadcast lenses, where cost is less of a consideration.

The FD 55mm f/1.2 AL, introduced in March 1971, marked Canon’s first use of an aspherical element in a production lens.

Plastic Molded Aspherical

Canon’s plastic molded aspherical elements (PMo) are created by precisely molding optical-grade plastic into aspherical shapes, offering a cost-effective alternative to glass lenses.

The use of plastic reduces lens weight and production costs, making high-quality optics more affordable for consumer lenses. While less durable than glass, these elements maintain good performance in budget-friendly designs. These elements are used throughout Canon's lineup.

Canon released this little Canon Snappy 50, which was the world’s first camera lens for 35mm full-frame to incorporate a PMo aspherical lens element. Even though it's not a lens, it's cool – so here it is.

Glass Molded Aspherical

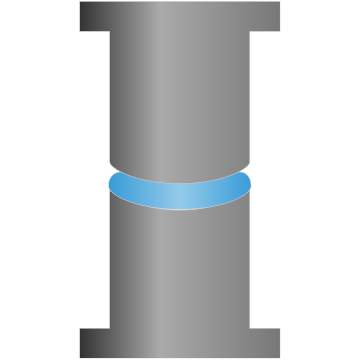

GMo aspherical lens elements are manufactured by softening glass material under high temperatures and then shaping it using a molding machine. These elements are suitable for large quantity manufacturing, the resulting lens element retains the scratch- and heat-resistant properties of glass.

Compared to precision grinding, glass molding is more cost-effective while maintaining excellent optical quality and durability. It allows Canon to incorporate aspherical elements into a wider range of lenses, balancing performance and affordability.

The Canon FD 35-105 f/3.5-4.5 was one of the first Canon lenses to have a Gmo element.

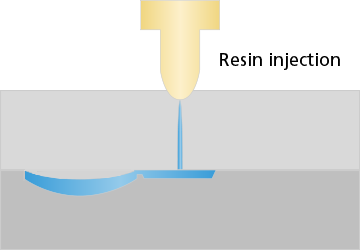

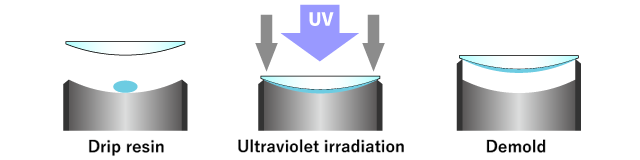

Replica Aspherical

Canon’s newest method is called replica aspherical elements. These are made by molding a thin optical resin layer onto a spherical glass base, thus creating the aspherical surface. This method is less costly than traditional grinding.

The technology reduces lens size and weight while maintaining performance, making it practical for a range of lenses, from budget to professional. It enables Canon to offer better optical quality at lower costs compared to fully ground aspherical lenses.

The earliest mention of a replica spherical element that I could find was the EF28-80mm f/3.5-5.6 II USM released in October 1993. Later versions are much more refined and accurate, such as the ones in the Z series RF zooms.

Fluorite

Canon's fluorite elements, crafted from synthetic calcium fluoride crystals, offer exceptionally low dispersion. Fluorite elements align the blue and red wavelengths to minimize chromatic aberration. Lighter than traditional glass, fluorite enables more compact super-telephoto lenses with large apertures with minimal chromatic aberrations.

The stones on the left are natural fluorite crystals. They are green and purple due to impurities within the crystals. In the middle is an artificial fluorite crystal ingot produced by Canon.

Canon’s lab-grown fluorite avoids the fragility and the rarity of pure natural crystals.

The first Canon lens to have a fluorite element was the Canon FL-F 300mm f/5.6 back in 1969.

UD (Ultra Low Dispersion)

UD (Ultra Low Dispersion) glass reduces chromatic aberration by aligning violet and red wavelengths. Less costly and more durable than fluorite, UD integrates into multi-element designs, minimizing lateral color shifts in zooms and teleconverters. Its low refractive index (around 1.5) supports slimmer lens profiles, while its scalability suits mass production.

When paired with aspherical elements, UD improves contrast and assists in delivering sharp edges without fringing. UD elements are widely used in Canon's lenses, even today.

The first example I could find of a lens with a UD element was the Canon FD 400mm F4L.

Super UD (Super Ultra Low Dispersion)

Super UD (Super Ultra Low Dispersion) glass approaches fluorite’s dispersion properties, and so, it very effectively reduces the chromatic aberrations. They are basically the equivalent of a pair of UD elements, which allows simpler, lighter designs for super-telephoto lenses.

There was a bunch of lenses that came out around the same time frame in 1993 that had the first examples of Super UD. Since this was way back 32 years ago, there's no real definitive “this was the first lens” even from Canon's own historical pages. From what I can gather, the coating appeared in 1993, and no lenses that came out prior to the EF 400mm f/5.6L USM would have needed a Super UD element. Especially noteworthy is that the lens, the EF 35-350mm f/3.5-5.6L USM, which came out in January 1993, didn't have any. So I think it's safe to assume that the EF 400mm f/5.6L USM is the first known example of a Super UD element, until someone proves me wrong in the forums.

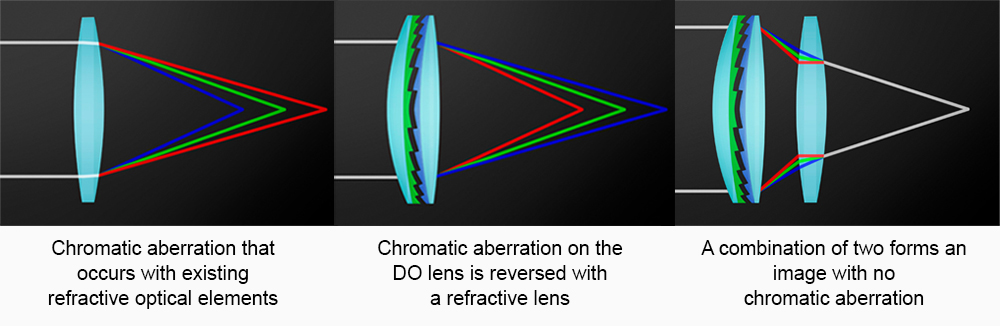

DO (Diffractive Optics)

Diffractive Optics (DO) elements use microscopic gratings etched into glass to diffract light, correcting chromatic errors. Unlike refractive lenses, DO elements enable super-telephoto lenses up to 50% shorter than traditional designs. Multi-layer DO stacks gratings to minimize flare and align wavelengths.

Despite minor light loss, the ability to make lenses smaller makes DO ideal for sports photography. The downside is that DO lenses usually exhibit non-optimum bokeh, but progressive DO element designs have reduced this artifact significantly over older generations.

The Canon EF 400mm F/4 DO IS USM was the first release in December 2001.

BR (Blue Spectrum Refractive)

Blue Spectrum Refractive (BR) elements use organic resin films with anomalous dispersion pto refract blue light (450nm) up to 1.5x more than red, countering secondary chromatic aberrations. Positioned between concave and convex glass elements, BR reduces blue fringing in high-contrast edges, especially important in fast primes. Its eco-friendly synthesis aligns with sustainable production, which has become more important in recent times.

Canon EF 35mm F1.4L II USM was the first example of a BR element.

Coatings

SC (Spectra Coating)

Spectra Coating (SC) is Canon’s first anti-reflective coating, which applies a single-layer film to lens surfaces. Spectra coatings on lenses helped reduce reflections and assisted in minimizing ghosting and flare.

Spectra Coating helped preserve neutral color rendition, which is very important for film photography. In Canon’s FD era, SC was Canon's standard. It helped enhance image quality for entry-level and mid-range lenses.

Canon's SC coatings were replaced in the 1970s with SSC (Super Spectra Coatings), which are still in use today.

SSC (Super Spectra Coating)

To talk about SSC coatings, we have to go back in time. Far back.

During the 1960s, when professional photographers were first beginning to use colour reversal film, Canon set its own standard for reproducing colours. Canon started with the notion that every lens should achieve the same reproduction of colour. However, to evaluate the accuracy of a lens’s colour reproduction, one must establish some standards for colour reproduction and balance. To begin with, Canon studied the differences in the characteristics of sunlight, especially the changes in sunlight throughout the year, as a function of air quality and angle of the sun, and they used that as a basis to create their colour calibration.

Canon’s research not only included repeated test photos, but they also asked for the opinions of many panelists. The data that Canon acquired through this process was eventually turned into numeric values, which established Canon’s own colour reproduction standard for lenses.

In the 1980s, the photographic community introduced the ISO colour Contribution Index as a new standard; however, the values given to these colours were very similar to those being put forth by Canon. There were still some values between the two standards that still differed as well, but Canon's standards required stricter tolerances.

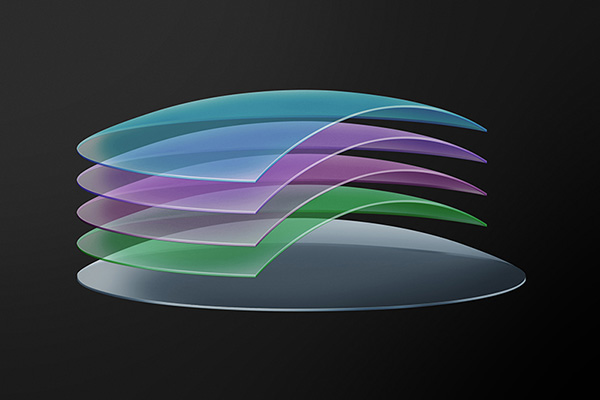

Canon created Super Spectra Coating (SSC) in order to fulfil this standard for colour reproduction. The multi-layer coating produces a tough lens surface with consistent optical properties, combined with a low likelihood of lens flare and ghosting due to reflections on the surface of the lens.

The first example I could find, but there may be more, two lenses were released at what seemed to be around the same time. The Canon FD 55mm F1.2 and the Canon FD 55mm F1.2AL that we previously talked about were both released in March 1971, and are the earliest examples of SSC coatings that I could find.

Oh, and before someone says, they didn't have SSC because it doesn't say it on the lens. That is correct. Canon didn't start identifying SSC on the lenses until after (even though some images of the FD 55mm F1.2 non-aspherical seemed to have SSC, but that may have been a later batch), but I looked it up in the chart from the F-1 brochure from 1971. I offer many thanks to the guy who scanned that document because I was starting to lose my mind.

SWC (Subwavelength Structure Coating)

SWC (Subwavelength Structure Coating), developed by Canon, is a new type of technology that utilizes aluminum oxide (Al2O3) as the structural material of the coating to align countless wedge-shaped nanostructures only 220 nm high, smaller than the wavelength of visible light, on a lens element. This coating at the nano-scale provides a smooth transition between the refractive indexes of glass and air, eliminating the boundary between the substantially different refractive indexes.

Additionally, it has shown surprising reflection-prevention performance even with light that has particularly large angles of incidence, something that has never been seen with a conventional coating. SWC is now being used in a wide variety of lenses in addition to wide angle lenses.

Additionally, large-diameter super telephoto lenses have also greatly reduced the incidence of flare and ghosting due to incident light reflecting near the peripheral area, which was previously difficult to avoid.

The Canon EF 24mm F1.4L II was the first Canon lens with SWC coatings.

ASC (Air Sphere Coating)

ASC represents a technology that utilizes a thin film consisting of both silicon dioxide (SiO2) and air deposited on top of the vapor-deposition lens coating. ASC reduces reflections by applying a precise combination of air, which possesses a much lower refractive index than optical glass, to achieve the ultra-low refractive index in that coating layer.

ASC demonstrates impressive anti-reflective performance, especially for incidental light arriving at an angle nearly perpendicular to the lens. ASC, like SWC, suppresses secondary reflections of light arriving at acute angles of incidence and supports any light by suppressing all extraneous light that comes into the lens regardless of the incoming angle, and alleviates lens flares and ghosting. Because ASC can be effective on a variety of curved surfaces, it is relatively less limiting to lens design.

The Canon EF100-400mm f/4.5-5.6L IS II USM was the first lens to use the ASC coatings.

Fluorine Coating

A fluorine coating is applied over the anti-reflective coating on the lens surface for easy removal of dirt from the lens. The coating is highly functional with a great level of oil and water repellency, while still being optically clear. Any smudge or oil on the lens surface can be wiped away without lens cleaner or solvents, just using a dry cloth. Dry-wiping leads to less static electricity, plus the ultra-smooth surface does not scratch as easily.

The Canon EF70-300mm f/4-5.6L IS USM was the first Canon lens to receive fluorine coatings.

DS(Defocus Smoothing)Coating

There is one coating that has nothing to do with controlling lens flare, ghosting, or even aberrations, but its job is to really add to the final image. That is the defocus smoothing coating or DS.

The first image is an atypical standard element, and the second image shows that image with Canon's DS coating. What this does is give Bokeh a round, soft effect, instead of hard transitions.

This is relatively new to Canon, and it's a vapor-deposited coating that offers a soft defocus rendering effect. With this coating, a well-defined outline in a defocused image is smoothly blurred. When DS coating is applied on the lens surface, its coating structure is designed to control the amount of light passing through the lens and then decrease the light transmittance gradually from the lens's center to its peripheral area. Consequently, the amount of detail and definition in the outline at the defocused portion of an image can be smoothly blurred.

The Canon RF 85mm F1.2L USM DS was the first Canon lens to employ the DS coatings.

Final Thoughts

Canon’s lens elements and coatings illustrate Canon's continual advancements in optical technology. Canon has shifted from the base technologies of the FD era to the current RF system's new technologies. Elements are developed to resolve specific optical issues, from chromatic aberrations to spherical aberrations, and also to ensure the lens delivers quality optical results, for the price.

Canon will undoubtedly continue to develop new technologies and improve lenses even further than what we are seeing today.

As a side note, this article has really shown me that Google search's AI is having some serious issues. I think it was right 5% of the time, especially when I had to go back 30-40 years to find data.