Darkmatter said:

Even though you don't think you're moving your eyes when looking at clouds and tree bark, you more then likely are, just a small amount, and at hard to notice speeds. You're so used to this process that its not something you can be sure that you would notice, since you normally don't. You're brain combines all these part images together to give you what you perceive as "the world." It is also very possible that you aren't truly seeing the bark. You've seen it many times before, even if you don't realize it. You're brain will often fill in information that it isn't actually "seeing" at that very moment because it either knows that it is there, or that it believes that it is there. This is one of the reasons why eye witness accounts of sudden and traumatic crimes can be notoriously inaccurate. As an example, a person may honestly believe that a mugger has a gun in his one hand that is down at his side near his (the robbers) pocket, but in reality what is there is a dark pattern on his jacket pocket, either from the jacket's colour/style, or from a shadow. The witness isn't lying, he was just so afraid for his/her life that he/she imagined that there was a gun there.

Your talking about a different kind of eye movement, but you are correct, our eyes are always adjusting.

Regarding eye-witness accounts...the reason they are unreliable is people are unobservant. There are some individuals who are exceptionally observant, and can recall a scene, such as a crime, in extensive detail. But how observant an individual is, like many human things, falls onto a bell curve. The vast majority of people are barely observant of anything not directly happening to them, and even in the case of things happening to them, they still aren't particularly clearly aware of all the details. (Especially this day and age...the age of endless chaos, immeasurably hectic schedules, and the ubiquity of distractions...such as our phones.)

I believe the brain only fills in information if it isn't readily accessible. I do believe that for the most part, when we see something, the entirety of what we see is recorded. HOW it's recorded is what affects our memories. For someone who is attuned to their senses, they are evaluating and reevaluating the information passing into their memories more intensely than the average individual. The interesting thing about memory, it isn't just the act of exercising it that strengthens it...it's the act of evaluating and

associating memories that TRUELY strengthens them. Observant individuals are more likely to be processing the information their senses pick up in a more complex manner, evaluating the information as it comes in, and associating that new information with old information, and creating a lot more associations between memories. A lot of what gets associated may be accidental...but in a person who has a highly structured memory, with a strong and diverse set of associations between memories, one single observation can create a powerful memory that is associated to dozens of other powerful memories. The more associations, the more of your entirety of memory that will get accessed by the brain, and therefor strengthened and enhanced, than when you have fewer associations.

I actually took a course on memory when I first started college some decade and a half ago. The original intent of the course was to help students study, and remember what they study. The course delved into the mechanics and biology of sensory input processing and memory. Memory is a multi-stage process. Not just short term and long term, but immediate term (the things you remember super vividly because they just happened, but this memory fades quickly, in seconds), short term, mid term, and long term (and even that is probably not really accurate, it's still mostly a generalization). Immediate term memory is an interesting thing...you only have a few "slots" for this kind of memory. Maybe 9-12 at most. As information goes in, old information in this part of your memory must go out. Ever have a situation where you were thinking about something, were distracted for just a moment, but the thing you were thinking about before is just....gone? You can't, for the life of you, remember what it was you were thinking about? That's the loss of an immediate term memory. It's not necessarily really gone...amazingly, our brains remember pretty much everything that goes into them, it's just that all the memories we create are not ASSOCIATED to other things that help us remember them. It's just that the thing you were thinking about was pushed out of your immediate-mode memory by that distraction. It filled up your immediate mode memory slots.

Your brain, to some degree, will automatically move information from one stage to the next, however without active intervention on your part, how those memories are created and what they are associated with may not be ideal, and may not be conducive to your ability to remember it later on. The most critical stage for you to take an active role in creating memories is when new information enters your immediate term memory. You have to actively think about it, actively

associate it with useful other memories. Associations of like kind, and associations of context, can greatly improve your ability to recall a memory from longer term modes of memory storage. The more associations you create when creating new memories, the stronger those memories will be, and the longer they are likely to last (assuming they continue to be exercised). The strongest memories are those we exercise the most, and which have the strongest associations to other strong memories. Some of the weakest memories we have are when were simply not in a state of mind to take any control over the creation of our memories...such as, say, when a thug walks in and puts a gun in someone's face. Fear, fight or flight, activities kicked into gear by a strong surge of hormones can completely mess with our ability to actively think about what's going on, and instead...we react (largely out of 100% pure self preservation, in which case if we do form memories in such situations...they are unlikely to be about anyone but one's self, and if they are about something else, they aren't likely to be very reliable memoreis.)

It was one of the best courses I ever took. Combined with the fact that I'm hypersensitive to most sensory input (particularly sound, but sight and touch as well...smell not so much, but I had some problems with my nose years ago), the knowledge of how to actively work sensory input and properly use my memory has been one of the most beneficial things to come out of my time in college.

If you WANT to have a rich memory, it's really a matter of using it correctly. It's an active process as much as a passive one, if you choose to be an observant individual. If not...well, your recallable memory will be more like swiss cheese than a finely crafted neural network of memories and associations, and yes...the brain will try to fill in the gaps. Interestingly, when your brain fills in the gaps, it isn't working with nothing. As I mentioned before, we remember most of what goes in...it's just that most of the information is randomly dumped, unassociated or weakly associated to more random things. The brain knows that the information is there, it just doesn't have a good record of where the knowledge is. I don't think that really has to do with the way our eyes function...it has to do with how the brain processes and stores incoming information. Our eyes are simply a source of information, not the tool that's processing and storing that information.

Darkmatter said:

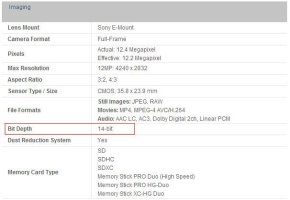

Probably the only real, reliable way to conduct an experiment like looking at a very dark and a very bright thing at the same time and knowing that you didn't look at each separately would be to have a special camera/s closely monitoring your head, eyeballs, and pupils for any movement. It would also have to be an artificial or set up scene so that there was some symbol or something in the dark area that you would have to be able to identify without any movement. I honestly don't think "not moving" at all is possible without medical intervention such as somehow disabling a persons ability to move at all; body, neck, head, even eyeballs.

Not exactly a fun experiment.

You do move your eyes, a little. You can't really do the experiment without moving back and forth. The point is not to move your eyes a lot. If you look in one direction at a tree, then another direction at the cloud, your not actually working within the same "scene". In my case, I was crouched down, the tree in front of my, the cloud just to the right behind it. Your whole field of view takes in the entire scene at once. You can move your eyes just enough to center your 2° foveal spot on either the shadows or the cloud highlights, but don't move around, don't move your head, don't look in a different direction, as that would mess up the requirements of the test. So long as "the scene" doesn't change...so long as the whole original scene you pick stays within your field of view, and all you do is change what you point your foveal spot at, you'll be fine.

To be clear, a LOT is going on every second that you do this test. Your eyes are sucking in a ton of information in tiny fractions of a second, and shipping it to the visual cortex. Your visual cortex is processing all that information to increase resolution, color fidelity, dynamic range, etc. So long as you pick the right test scene, one which has brightly lit clouds and a deep shaded area, you should be fine. In my experience, when using my in-camera meter, the difference between the slowest and fastest shutter speed is about 16 stops or so. I wouldn't say that such a scene actually had a full 24 stops in it...that would be pretty extreme (that would be another eight DOUBLINGS of the kind of tonal range I am currently talking about...so probably not a chance). But I do believe it is more dynamic range than any camera I've ever used was capable of handling in a single frame.